Destroy, Rebuild, Until God Shows

How the Berlin Conference carved up Africa for Imperial gain.

Otto Van Bismarck, Chancellor of the German Empire, following the victorious outcome of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, was a skilled diplomat for his time.

Bismarck’s policy design and ambition for Germany’s seat at the table among the fellow European empires allowed Germany to command respect after defeating France, but also required diplomatic precision amongst paranoid leadership in Russia, Britain, and France.

“Laws are like sausages — it’s best not to see them being made.” - Otto Von Bismarck, German Chancellor.

After Germany’s ascension among the elites of the European empires in the mid-1870s, imperialism in foreign policy and ambition had formed a feverish sentiment among the traditional powers of Britain and France.

The annexation of Alsace-Lorraine by Germany after defeating France sparked intense fears of further foreign annexation of currently unclaimed territories, particularly in Africa.

In Richard J. Evans’ book The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914, he describes the growing paranoia explicitly:

“International rivalries intensified, as the slow but steady expansion of European possessions overseas began to create collisions between rival European powers, for example, in West Africa between the British, the French, and the Belgians.” - p. 644

The Alsace-Lorraine annexation truly set in motion an imperial movement that would set the stage decades later for the outbreak of World War I.

Your Land Is My Land

Britain boastfully claimed territory in India in 1877, proclaiming Queen Victoria as Empress of India, while Italy publicly pushed imperial desires in Mediterranean territory.

Still seething over lost territory at the hands of the Germans, France declared its intentions to acquire further territory.

Bismarck, a man who envisioned German expansion through diplomacy rather than war, could feel the temperature rising between the European powers. He decided to use his diplomatic acuity and negotiate a meeting to put in writing the intentions of how the powers could achieve their expansion goals and avoid military conflict.

To Bismarck, the conference's goal was to determine a formal declaration of interests from each of the powers.

How Africa became a central desire for the power players in Europe is a long and winding thread with too much depth to be explained in the detail it deserves in this article.

To summarize, both the British and the French became entangled in African affairs after the creation of the Debt Commission, a supervision decree set up to oversee loan repayments to European governments by Egypt, which was embarking on modernization projects such as the creation of the Suez Canal, construction of railroads, telegraph lines, and irrigation systems.

Outside of Britain and France’s involvement in Egypt’s debt accumulation, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Russia, and Germany all became overseers of the Debt Commission between 1877 and 1885.

We’ve mentioned before that Bismarck was a motivated diplomat. He saw this web of conflict, specifically between the British and the French, as an opportunity to use his political acumen to pit the powers against one another and provide security for Germany.

Richard J. Evans provides a visual in Pursuit of Power:

“Anglo-French clashes over these issues were exploited in 1884 by Bismarck, who backed the French to try and draw them away from thoughts of taking revenge over Germany for the loss of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871. At the same time, he also wanted to show the British the desirability of being nice to the Germans by annoying or threatening them in colonial matters.” - p. 646

Evans describes Germany’s public declarations of territories in Africa ahead of the Berlin Conference, notably in Cameroon, New Guinea, and German East Africa (including present-day Tanzania, not including Zanzibar).

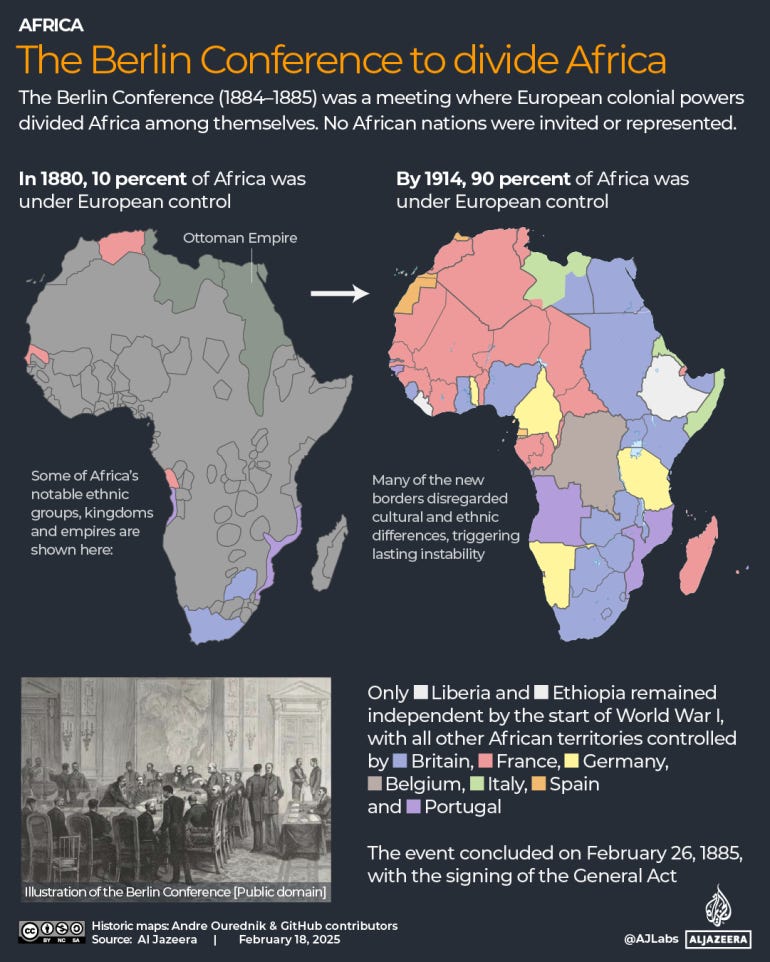

This rush of foreign acquisition among the European powers, now formally known as the ‘Scramble For Africa’, was formalized by the discussions and outcomes of the Berlin Conference, held November 15, 1884, and February 26, 1885.

For all of Bismarck’s diplomatic prowess, he was not absolved from error. Since the unification of Germany in 1871, Bismarck had intentionally designed his foreign policy around alliances and exchanges.

The Three Emperors’ League was created in 1873, tying Germany to allegiances with Austria-Hungary and Russia — two empires with ambitious desires in the Balkan region — created a ‘double-edged policy that aimed, on the one hand, to avoid direct confrontations between Germany and other major powers, and, on the other, to exploit the discord among the other powers whenever possible for Germany’s advantage.’, as described by Christopher Clarke in his book Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went To War In 1914.

In 1882, Bismarck formed the Triple Alliance, a mutual defense agreement between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. This was an extension of the dual alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1879, as a defense agreement against Russia, due to the aforementioned mutual interests between Austria-Hungary and Russia in the Balkan region. Italy joined the alliance in 1882, after a military conflict with France over claimed control over Tunis (modern-day Tunisia).

That’s My Map of Africa

Imagine laying tracing paper over the continent of Africa.

Typically, you would trace the outside border and begin to trace the internal borders for a full 1:1 replica of the existing territories. During the Berlin Conference, the imperial leaders carved up, reshaped, and repurposed Africa in their own image.

“Your map of Africa is really quite nice. But my map of Africa lies in Europe. Here is Russia, and here... is France, and we’re in the middle — that’s my map of Africa” - Bismarck told an explorer in 1888.

As ambitious as Bismarck was, his shortsighted approach to diplomacy would ultimately open a Pandora’s Box at the Berlin Conference.

Bismarck felt the Berlin Conference would be an opportunity to showcase advancement among the traditional European powers, and solidify Germany’s conservative party against a parliament that was growing more frustrated with what they felt was halted progress, due in part to Bismarck’s foreign policy tying them to countries they otherwise could be more aggressive with in their goal for colonial expansion.

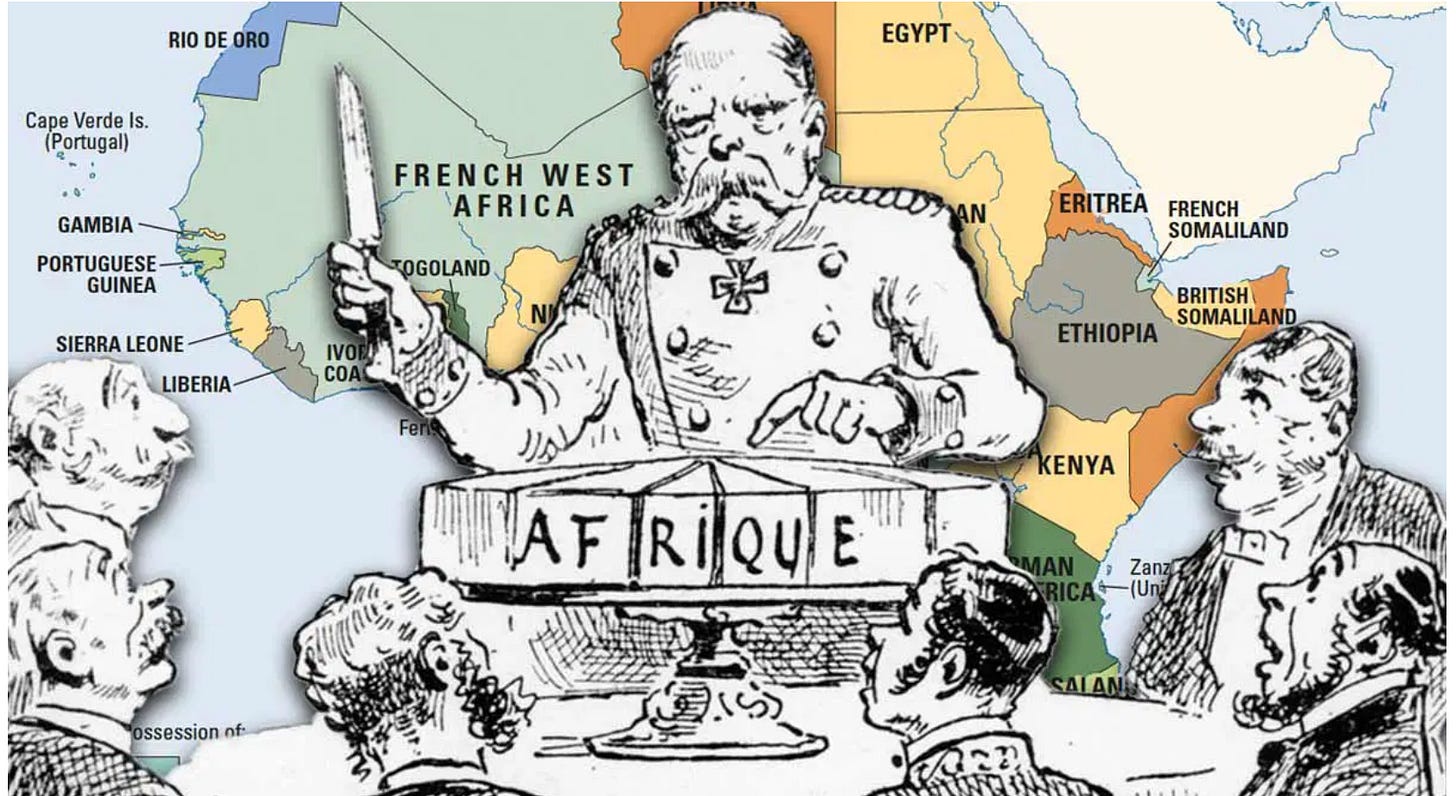

The Berlin Conference proved to be an unmitigated disaster for Germany and Bismarck. Of the 14 countries represented at the conference to colonize Africa (surprise, Africa was not represented), Germany left almost nothing gained besides the territories they had previously claimed. In contrast, the British and French left the conference as if they had emptied a bank vault.

The outcome of the Berlin Conference would have unprecedented ramifications for the future of Africa in the decades to come.

While most of the “ownership” decisions were determined during the conference, action on those would not come until much later, and some not until after the Great War in 1918.

Throughout the four months of the conference, discussions and negotiations took place to decide who would own what and what territories belonged to what empire.

The following list outlines the territories claimed by the countries in attendance.

France: French West Africa (Senegal), French Sudan (Mali), Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), Mauritania, Federation of French Equatorial Africa (Gabon, Republic of the Congo, Chad, Central African Republic), French East Africa (Djibouti), French Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Dahomey (Benin), Niger, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Libya

Britain: Cape Colony (South Africa), Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Bechuanaland Protectorate (Botswana), British East Africa (Kenya), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), Nyasaland (Malawi), Royal Niger Company Territories (Nigeria), Gold Coast (Ghana), Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (Sudan), Egypt, British Somaliland (Somaliland)

Portugal: Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique), Angola, Portuguese Guinea (Guinea-Bissau), Cape Verde

Germany: German Southwest Africa (Namibia), German East Africa (Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi), German Kamerun (Cameroon), Togoland (Togo)

Belgium: Congo Free State (Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Italy: Italian Somaliland (Somalia), Eritrea

Spain: Equatorial Guinea (Rio Muni)

The General Act, a treaty that served as the formalization of discussions and negotiations that were agreed upon during the conference, stated six goals the powers intended to see through, as listed below:

A Declaration relative to freedom of trade in the basin of the Congo, its embouchures and circumjacent regions, with other provisions connected therewith.

A Declaration relative to the slave trade, and the operations by sea or land which furnish slaves to that trade.

A Declaration relative to the neutrality of the territories comprised in the Conventional basin of the Congo.

An Act of Navigation for the Congo, which, while having regard to local circumstances, extends to this river, its affluents, and the waters in its system (eaux qui leur sont assimilées), the general principles enunciated in Articles 58 and 66 of the Final Act of the Congress of Vienna, and intended to regulate, as between the Signatory Powers of that Act, the free navigation of the waterways separating or traversing several States - these said principles having since then been applied by agreement to certain rivers of Europe and America, but especially to the Danube, with the modifications stipulated by the Treaties of Paris (1856), of Berlin (1878), and of London (1871 and 1883).

An Act of Navigation for the Niger, which, while likewise having regard to local circumstances, extends to this river and its affluents the same principles as set forth in Articles 58 and 66 of the Final Act of the Congress of Vienna.

A Declaration introducing into international relations certain uniform rules with reference to future occupations on the coast of the African Continent.

The Lagos Observer newspaper lamented, one week before The General Act was ratified, that “the world had, perhaps, never witnessed a robbery on so large a scale.”

What would happen to Africa in the coming years is a pillage to a continent at scale, unlike anything seen in modern history.

Before the Berlin Conference, it was estimated that roughly 20% of Africa, particularly coastal regions, was already under colonization.

By 1890, the countries present at the Berlin Conference had colonized roughly 90% of African territory.

Previous agreements made before, during, and after the conference's conclusion were intended to suppress the African slave trade and maintain order in the existing societies and cultures. It’s widely believed that this was disregarded mainly among most, if not all, countries represented at the conference.

The most notable fallout of the carving of Africa in 1885 was King Leopold II of Belgium’s insistence on not only maintaining control of the inland Congo Free State, but ensuring no other powers interrupted his access in and out of the territory. A territory that was acquired through his own shrewd diplomatic efforts.

Leopold sent representatives to Berlin on his behalf to convince the European powers that the Congo Free State was non-negotiable territory, as he had already begun “humanitarian efforts” there, and his investments both financially and in the territory were too great to interfere with.

While Leopold would never step foot in Africa, the terror he would oversee is often attributed to fiction.

Using a mercenary force to oversee operations in the Congo, Leopold extracted ivory and rubber in the late 1800s through the use of forced labor on the Congolese people.

Historians have attributed heinous acts of violence against the Congolese people under the direction of Leopold, including the murder of women and children, and the removal of limbs to Congolese workers if rubber quotas were not met.

While historians have argued over the true number of deaths under the reign of Leopold in Congo, the estimates hover around 10 million.

Former Civil War veteran and member of the Ohio House of Representatives, George Washington Williams, was one of the first to use the term ‘Crimes Against Humanity’ when describing the reign of terror by Leopold in Congo.

So much of the world has been reimagined since the outbreak of World War I, and so much of it because of the decisions made in the decades before the first shot was fired in 1914.

There are an infinite number of events, decisions, handshakes, and blind ambitions that played a role in the outbreak of global conflict in Europe in 1914, but the scramble for Africa and the Berlin Conference are two events that, when tied together, crystalize to show a continent of powers not operating in a peacetime manner.

Thank you for taking the time to read this lengthy piece. Since I’ve started this Substack, I’ve intended to use it to reignite my passion for writing, exploring, and analyzing periods and people of history through an objective lens.

I hope this showcase works like that and helps highlight the human history I believe is critical to remember and revisit.

My goal is to continue to provide work like this regularly, but also offer shorter, more digestible content that can still highlight moments and people in history worth revisiting and discussing.

This article couldn’t have been written without the knowledge gained from the reading I’ve done lately, so I would be remiss if I didn’t share some of the source work below:

Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went To War In 1914 by Christopher Clarke

The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914 by Richard J Evans

King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild

Blood and Iron: The Rise and Fall of the German Empire 1871-1918 by Katja Hoyer

“A Robbery on so Large a Scale”: 140 Years after the Berlin West Africa Conference by Chidi Anselm Odinkalu and Chepkorir Sambu

Colonising Africa: What Happened At The Berlin Conference? By Shola Lawal

This is from Scroll XVI of my project The Hidden Clinic. I wrote it as a prayer—not a statement. Not for applause. Just rhythm for witness. https://thehiddenclinic.substack.com/p/to-the-ones-who-were-set-on-fire