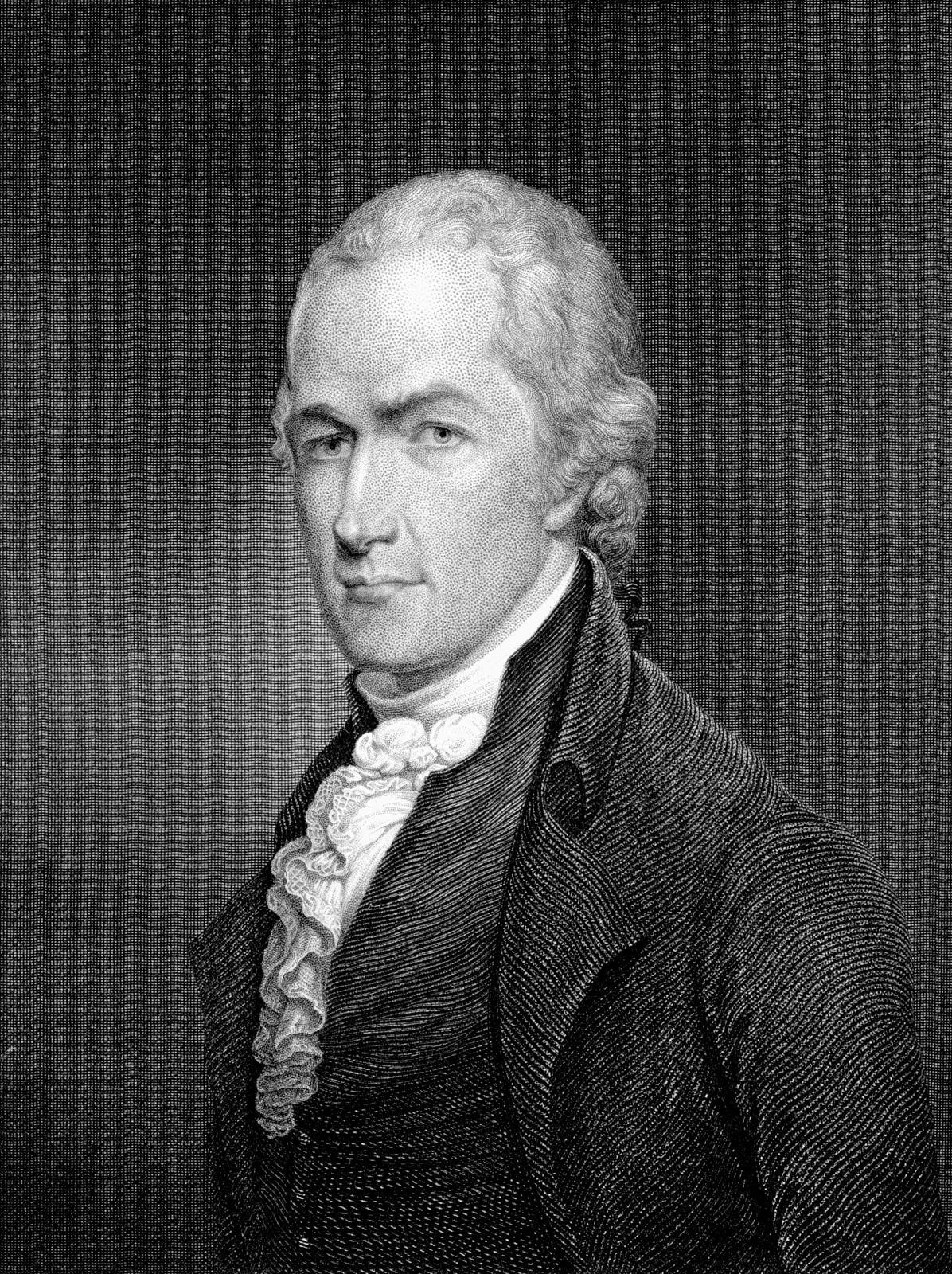

More than any other Founder, Alexander Hamilton believed the Constitution must be a machine of energy.

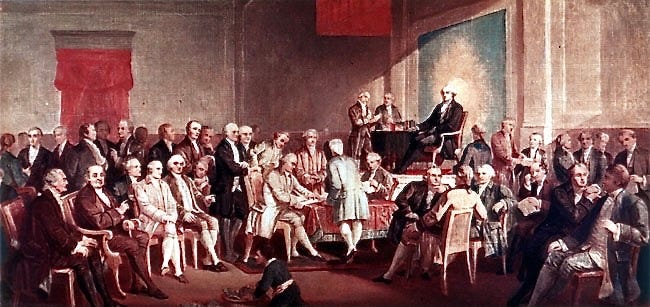

As delegates made their way to Philadelphia in 1787 for what they thought would be a meeting to discuss changes to the existing governing document of the newly independent free states of America, the Articles of Confederation, Hamilton was surmising an entirely different objective.

Hamilton, convinced that weak institutions, not overbearing ones, are what destroy republics. The Articles of Confederation, in his view, had proven that liberty without power was chaos.

This article marks the beginning of a series on the ideologies and obsessions of the Founding Fathers. Hamilton, Madison, Jefferson, Adams, and Washington, among other characters, and how they shaped the Constitution.

We start with Hamilton, whose fierce ideologies and prolific writings pressed forcefully for a vigorous, centralized republic.

At the center of Hamilton’s political thought was a paradoxical belief that government must be strong if liberty is to endure.

In Federalist No. 70, he famously declared:

“Energy in the Executive is a leading character in the definition of good government. It is essential to the protection of the community against foreign attacks… to the steady administration of the laws… to the security of liberty.”[^1]

Unlike Jefferson, who equated liberty with limited authority, Hamilton argued that only a government with real force could preserve property, ensure stability, and command respect abroad against a fractured state system that Hamilton raged would collapse into anarchy.

Hamilton’s writings reveal a deeply skeptical view of human nature; In Federalist No. 15, he condemned the Articles of Confederation as a ‘childish system’ that assumed good will alone would bind the states:

“It is essential to the idea of a law that it be attended with a sanction; or, in other words, a penalty or punishment for disobedience. This penalty, whatever it may be, can only be inflicted in two ways: by the agency of the courts and ministers of justice, or by military force; by the coercion of the magistracy, or by the coercion of arms.”[^2]

For Hamilton, governments that relied on voluntary compliance or the virtue of citizens were doomed, like those of ancient Greece and Rome.

His vision of a successful government demanded structures that could compel obedience, not share in it’s powers with the common folk. Hamilton envisioned a government led by courts with authority, an executive branch armed with centralized force, and a legislature with supremacy over weak and selfish state ideologies.

At the Philadelphia Convention in June 1787, Hamilton shocked his colleagues by proposing a system modeled partly on Britain - the very same Britain that men he stood amongst fought against for American independence.

The delegates arrived in Philadelphia under the assumption that they were going to collectively work towards amending the current state of the Articles of Confederation, not wholly disband it in favor of an entirely new governing document - what would become the Constitution of The United States of America.

Advantage Hamilton.

Hamilton proposed ideas for a federal government that at the time seemed wholly contrarian to the independence movement. The belief that a President should serve for life, Senators also should hold a lifelong tenure, and a strong central government that could veto state laws with supreme authority.

James Madison, who took notes on not just proceedings, but debate speeches to ensure these critical discussions wouldn’t become hearsay if the fate of the government in the future hung in the balance, preserved Hamilton’s words regarding his undoubted affection for Britain.

“The British Government was the best in the world: and that he doubted much whether anything short of it would do in America… He was therefore for a general government, strong enough to unite the people and compel their obedience.”[^3]

Delegates present in Philadelphia dismissed Hamilton’s plan as idealistic and contrarian to the independence cause they fought so valiantly for.

Yet Hamilton’s intervention set a benchmark that would not be ignored.

If his radical proposal was unpalatable, then the Convention’s eventual compromise of a single energetic executive and a bicameral legislature with broad national powers would suddenly seemed moderate.

Advantage Hamilton.

Despite considerable pushback, Hamilton held firm in his beliefs of what a successful government entailed in his writings.

Hamilton authored 51 of the 85 Federalist Papers, the most sustained series of political arguments in American history.

The necessity of federal supremacy (Nos. 15–17) and the belief that only a national government with direct authority over individuals could function. Hamilton pressed on the dangers of anarchy (Nos. 21–22), stating that without central power, states would spiral into rivalry and violence.

Hamilton believed that a single executive (Nos. 70–72) was not a threat to liberty but its guardian.

Where Hamilton arguably faced the most significant challenge was his ideology regarding the financial basis of union, where national taxation powers were essential to stability and credit. (Nos. 30-36)

Hamilton’s vision of the Constitution saw the creation of a strong, centralized republic capable of governing a fractured and scattered nation.

“The vigor of government is essential to the security of liberty.”

— Federalist No. 1, 1787

At New York’s ratifying convention, where Anti-Federalists nearly blocked ratification, Hamilton argued relentlessly for national authority.

According to one delegate’s notes, Hamilton reminded the assembly:

“To balance a large state against a small one is impossible. We must abandon the vain project of legislating for states in their collective capacities, and adopt one of legislating for individuals.”[^4]

Hamilton was the Constitution’s most relentless pursuer, ensuring its survival in New York, a powerful and crucial piece of his ideological philosophy.

Hamilton’s ideology of an energetic executive, strong central government, distrust of pure democracy, emphasis on national credit and stability, did not dominate the Convention, but it had a profound impact on what the Constitution came to be.

Where Madison supplied the architecture of checks and balances, Hamilton supplied the insistence on vigor.

Where Jefferson romanticized liberty, Hamilton insisted it required force.

Where Adams feared aristocracy, Hamilton feared anarchy.

Hamilton held no fear of expressing his vision of how the powers should be distributed. Hamilton believed in the Presidency acting as a single, independent executive with defined powers.

He believed in federal supremacy, backed by the Constitution as the supreme law of the land.

Hamilton’s vision would later hold influence over decisions like McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), where the Supreme Court upheld implied powers. an argument Hamilton himself had made for the Bank of the United States.

Hamilton’s contribution to the Constitution was his ability to strike relentlessly at the weaknesses of a fractured nation state existence and demanded a government with the energy to survive beyond the turn of the decade.

Hamilton often referenced the fall of the Greek and Roman democracies as a stake in the ground for his strong beliefs in centralized executive power.

The ideologies driving Hamilton were explicitly clear: Liberty is not preserved by constraining power, but rather enhanced by centralizing it.

The Constitution, with its strong executive, independent courts, and supremacy over the states, reflects that vision as much as it reflects Madison’s balance or Jefferson’s ideals.

Hamilton foretold of a United States without a strong and powerful federal government…

“A nation without a national government is an awful spectacle.”[^5]

The Constitution became, in no small part, his remedy for that spectacle.

Footnotes

[^1]: Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 70, March 15, 1788.

[^2]: Hamilton, Federalist No. 15, Dec. 1, 1787.

[^3]: James Madison, Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, June 18, 1787.

[^4]: Debates of the New York Ratifying Convention, 1788.

[^5]: Hamilton to George Washington, Feb. 1787, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton.

If you enjoyed this piece, you might consider subscribing to get early access to all articles, and podcast episodes. As well as subscriber only access to curriculum for articles like these, and for the podcast episodes, including curated reading lists and more.